Thoughts On: Berlin Gallery Weekend 2018 (Part Four: Los Carpinteros)

Los Carpinteros

El Otro, El Mismo / The Other, The Same at KOW, Brunnenstrasse. 9, Berlin.

|

| Ceiba I (Image from KOW website) |

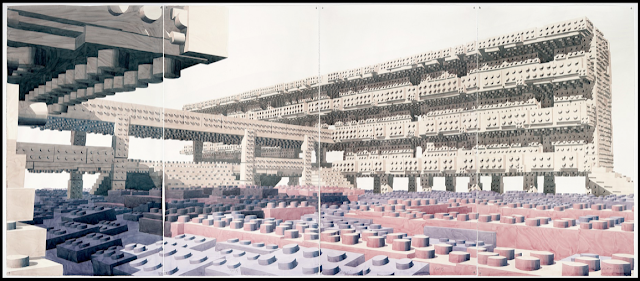

The gallery space was very differently presented from my previous visit to see Candice Breitz's Love Story in 2017. Then, I recall carefully descending into complete darkness, through a towering stage curtain, into a space completely dominated by Breitz's powerful video work. On this visit though, it is the sculpture Celosia Marroqui and that bright sunlight that dominate the main space. The hand crafted Moroccan tiles of Celosia Marroqui throw into sharp relief the poured concrete walls of the gallery; to the right, the quadricht Ceiba I (pictured above) hangs; upstairs visitors partake of the complimentary refreshments (it *is* an opening, after all); while downstairs, in that more familiar darkness, recent film works shock and absorb.

|

| Celosia Marroquí at KOW 2018 |

Los Carpinteros are interested in traces of human behaviour that they see left behind in objects - very often objects or buildings that are conceived with specific function. In 1961 an ambitious project was begun to found a multi-disciplinary Escuelas Nacionales de Arte in Havana - the principle building material being Terracotta Bricks. The school was envisioned to exalt, promote and demonstrate the ideas and virtues of the revolution in its infancy. But due to funds being diverted during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the schools were never finished. Though not explicitly referenced by Los Carpinteros, I feel that the Art School's half-built ruins of can hardly have escaped their cultural lexicon.

Compositionally, the the stark sunlight behind sculpture Celosia Marroqui mirrors the contrast of bricks against white paper in Ceiba I - a large watercolour of a Lego assemblage modelled on one of many abandoned school buildings in rural Cuba. The placement of Celosia Marroqui and Ceiba I together highlights the failed intention to fulfil the promise of prosperity and education for everyone: evidenced in the ruins not only of the Escuelas Nacionales de Arte, but the many rural schools dotted around the country. Through the mind's eye of Los Carpinteros we see structures refashioned from relics of failed promises, into malleable objects complete with the sense that you could rebuild or reshape and repurpose. These works give the clearest nod towards the idea that the ideals of Communism are still somewhat present within the fabric of Cuban society, waiting to be "bent back" into shape.

Downstairs, in a shift of tone and pace: there were three video works on show. I could not give Retractil (2018) my full attention because it featured the slaughtering of goats, but Comodato (2018) and Pallejo (2013) I watched through.

|

| Comodato (2018), Los Carpinteros (Image from contemporaryartdaily.com) |

The third film downstairs was Pallejo (2013) a black and white film featuring a couple in the midst of sex. At first, similarly to Retractil, I did not want to watch it. I questioned why there was something so graphic on show, and what the possible purpose of it could be. However, in the dutiful interests of research I took a break, re-read the press-release and put the provided headphones back on to attempt an understanding. The set and figures are softly lit, and as you watch the way that the bodies move together, you become slowly drawn into another dimension. Caught inside the frame and the camera-eye the bodies slowly change, and with this slow and meditative pace you begin to really focus on the way that the hands and skin have changed with age. You find yourself looking deeper, becoming quite fascinated with the way the differently shaped bodies fit together. Sex is an expression of humanity, an activity common across all cultures, and the reason most of us are here. Pallejo (I now know) means 'Skin', and that was what you began to focus on as the film progressed. The sex within the film could seem arbitrary or an unnecessary element purely added for shock value - but I asked myself what other activity could be common enough or leave it's participants vulnerable enough to open up that meditative moment leaving you nothing else to consider but the beauty of change within the human form that age brings.

El Otro, El Mismo / The Other, The Same references and draws on the history and culture of a country which is, for me, shrouded in unfamiliarity. To understand the work of Los Carpinteros I felt that I had to first understand much more about their societal background than the bare bones I already had. By the end of writing this, The Other might not have become quite The Same, but I certainly know more about Cuba than I did a week ago.

Further Reading:

- Los Carpinteros at KOW, Berlin (Press Release)

- Los Carpinteros at KOW (Contemporary Art Daily)

- Los Carpinteros Interview 2013 (Kunstverein Hannover)

- Havana's Forgotten Art Schools (Messy Nessy Chic)